Fashion has been given a bad name. All too easily it can bring to mind unemployed rich kids, jewel-bedecked magazine editors with botoxed foreheads, exploited models living off almonds and cigarettes, hordes of sycophantic bloggers and freakish clothes which cost more than a five star trip to Dubai. Despite popular misconceptions, however, there’s more to the industry than trust funds, vanity and Devil-Wears-Prada archetypes.

Fashion has been given a bad name. All too easily it can bring to mind unemployed rich kids, jewel-bedecked magazine editors with botoxed foreheads, exploited models living off almonds and cigarettes, hordes of sycophantic bloggers and freakish clothes which cost more than a five star trip to Dubai. Despite popular misconceptions, however, there’s more to the industry than trust funds, vanity and Devil-Wears-Prada archetypes.

I don’t need to tell you about the transformative power of clothing; you know that what you wear to a Friday morning lecture is going to differ from what you wear to a job interview, and you wouldn’t take the President so seriously if he delivered his speeches in a Juicy Couture tracksuit.

The word ‘fashion’ itself means to mould, to form, to shape. Just think of that overused metaphor which likens clothing to armour and makeup to war paint; it’s overused because it makes sense. Clothing can distinguish us, conform us, even change our shape and height. The effect which our clothing has on our mindset and behaviour is immeasurable. By dressing in any given way, we wield the power to change how we feel, how we are perceived and how we are treated.

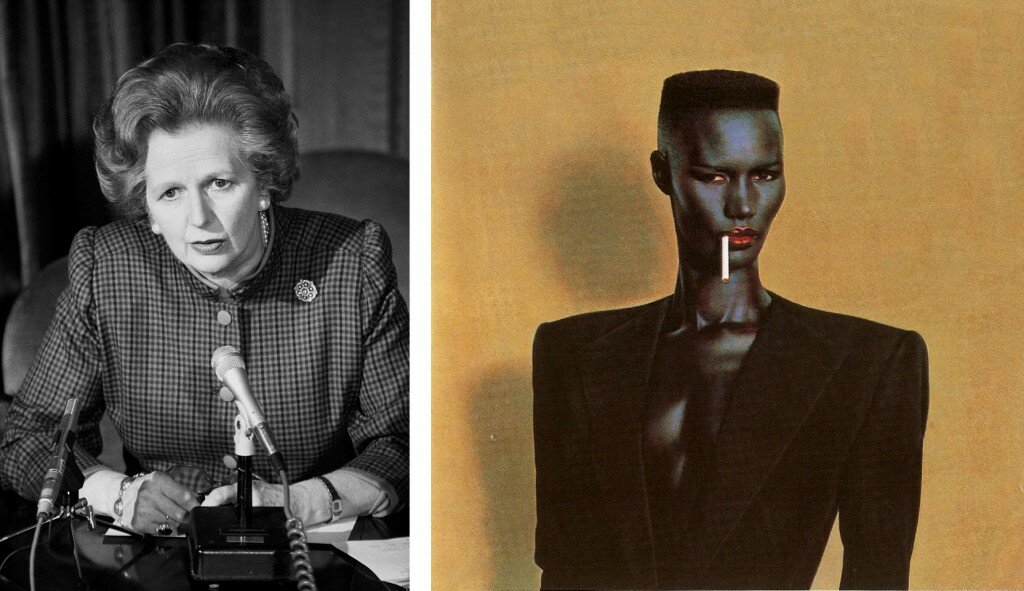

In 1975, John T. Molloy published an instructive book titled ‘The Women’s Dress for Success Book’, and the concept of ‘power dressing’ was born. Towering shoulder pads and angular tailoring took over the womenswear scene into the ‘80s, with influential figures such as Princess Diana, Grace Jones, and the cast of the bitchiest television show of all time, Dynasty, leading the way. Masculine silhouettes expressed a sort of sartorial feminism, setting out to assert the authority of high-achieving women in a man’s world. In a time when women were paid considerably less than men (a pay gap which is yet to close entirely) it was important for women to be taken seriously in the workplace. By appropriating masculine imagery traditionally synonymous with authority, women exploited the patriarchal hierarchy in order to empower themselves and demand respect.

Love her or hate her, we might see the late Margaret Thatcher as the mascot of ‘80s power dressing. As she climbed the career ladder, she acquired an exhaustive selection of suits and an increasingly voluminous helmet of hair. Like the colouring of a poisonous insect, her new look seemed to say ‘don’t mess with me,’ and put a firm middle finger up to the men who would sooner have her elbow-deep in Fairy liquid than running the country. Defence and attack were important in an environment as fiercely patriarchal as British Government. Thatcher once described her handbag as the only safe place in Downing Street, and to her credit, she fought her way right into its top seat.

While feminism became increasingly prevalent throughout the twentieth century, the power dressing phenomenon wasn’t limited to women. Its other proponents came from the world of popular music, with artists such as Boy George and David Bowie adopting drastically androgynous new styles, taking influence from previously underground trends and bringing them into the popular sphere, forging identities beyond the conventional.

However, fashion had political significance long before Ziggy Stardust descended from Mars. When Coco Chanel rid the world of the suffocating corset in the early 20th century, loose clothing became a symbol of the emancipation of women. They were no longer trussed up in whale-bone and dripping with heavy jewellery; they were free to move, to work, to think, and to possess a new, understated chic. Later on, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, clothing became an agent for the liberation of teenagers, with designers like Mary Quant bringing in the revolutionary mini-skirt, and far more drastically, with the opening of ‘SEX’, the avant-garde punk boutique conceived by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood in 1974. The punk movement expressed an anarchist belligerence and appropriated fetish clothing, bringing it out of sex clubs and into the public eye.

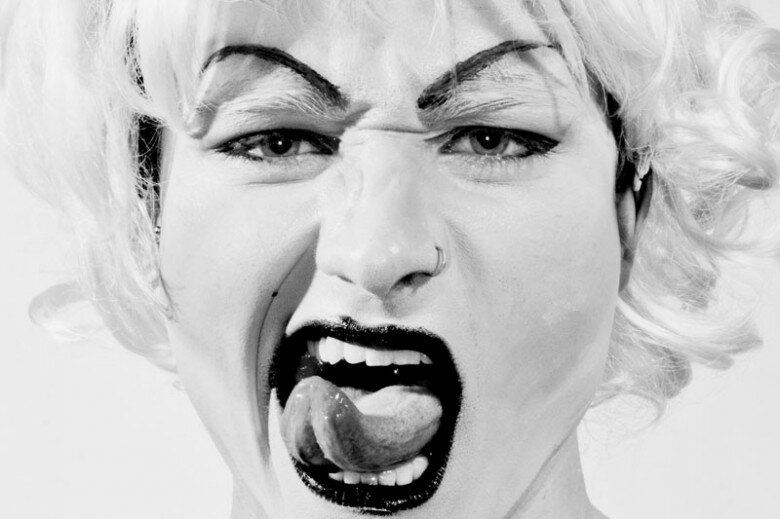

Although they only gained exposure over recent decades, underground styles such as fetish-wear had existed long before they were brought to the fore. Drag culture, perhaps harnessing the power of clothing and make-up more potently than any other discipline, is an example of another such subculture, finding increasing popularity with the majority.

Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary Paris Is Burning, filmed during the 1980s, explores the rich culture of drag balls in Harlem, New York. A drag ball is a competition in which contestants ‘walk’ a runway in outfits corresponding to a number of categories, such as ‘Parisian high fashion’, ‘butch queen, first time in drag at a ball’, and ‘vogue femme’. Participating drag queens often belong to collectives called ‘houses’, becoming ‘children’ to a ‘drag mother’ after whom the house is named. By walking in balls, they could win trophies and highly regarded accolades such as the ‘legendary’ title, and eventually the chance to become house mothers themselves.

The legendary queens of Paris is Burning

The drag lexicon, which was popularised by the documentary and, more recently, by the televised talent show RuPaul’s Drag Race, is particularly colourful. The best queens are ‘fierce’; the art of delivering scathing, witty insults is ‘reading’; to ‘beat one’s face’ is to apply immaculate make-up; to look good is to look ‘sickening’. A ‘kiki’ is a party, and a ‘kai kai’ is sexual encounter between drag queens – try not to confuse those two.

For a group of people who found it difficult to fit in with popular society and were often disowned by their families for their sexuality or transgender status, drag ball culture was an opportunity to be accepted, adored and rewarded. Still, it has never been without its perils.

Venus Xtravaganza, a regular on the ball circuit and one of Paris is Burning’s most celebrated subjects, was a transgendered woman saving up for sex-reassignment surgery. Like many drag queens, she resorted to prostitution as a means of income, devoid of other options due to the prejudice which had affected her upbringing. In 1988, her strangled body was discovered under the bed of a New York hotel room. The tragedy is relayed by Venus’ house mother in Paris is Burning, providing a startling reminder that, beyond the underground community which accepted people like her with open arms, the world isn’t always kind to those who refuse to conform to convention.

In her seminal 1990 work Gender Trouble, influential theorist Judith Butler wrote: “In imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself – as well as its contingency”. She argues that the performance of drag exposes gender for just that; a performance. It calls into question the relationship between sex and gender, a relationship ‘regularly assumed to be natural and necessary’, a ‘fabricated unity’. Typical transphobic polemic condemns cross-dressing as ‘unnatural’; Butler replies by asserting that no gendered behaviour is natural at all. It is, in fact, performance. In drag culture, a successful imitation is given the accolade of ‘realness’. It might at first seem paradoxical to call imitation ‘real’; however, the notion suggests that displaying an awareness of the construction of our outward façades – and the affectations which comprise them – is in fact more authentic than believing such façades to be natural.

Furthermore, drag can be seen to transcend the realm of gender. In the competitions documented by Paris is Burning, categories such as ‘executive realness’ entail dressing as successful, straight men, fulfilling a fantasy of acceptance, conformity and respect of the sort the LGBTQ population were rarely granted in the wider world.

Drag queen superstar RuPaul has said: ‘we’re born naked, and the rest is drag’, perhaps unwittingly recalling Simone de Beauvoir, who wrote: ‘One is not born a woman, but rather becomes one’. The same is true for all of us; our identities are constructed by experience, as well as prescribed by society. Although biological sex has become entangled with gendered behaviour, theorists such as Butler unsettle the bonds between them.

When we dress, we are making a plethora of references to every sartorial decision which has been made before us, all of which influence how we are perceived. Team a pair of jeans with a white t-shirt and a cigarette and you’re channelling James Dean macho; don a white halter-neck sundress and you’re referencing the voluptuous femininity of Marilyn Monroe; kitten heels with a circle skirt will take you straight to Stepford; a black dress and a cigarette holder will take you to Tiffany’s for breakfast. The lofty, glass-walled skyscrapers of the financial district will smile upon a Savile Row suit, and a glittering drag club in the centre of Harlem will have you however you are, sequins or not. Just be sure to keep it real.

All dressing is power dressing; clothing not only sits on our skin, but changes us from the inside out, shaping us into something beyond the corporeal – into signifiers of a long socio-political history and carriers of infinite connotations. So, if you’re ever tempted to disregard fashion as a shallow industry, remember that every sartorial decision you make is quietly monumental, entering you into an age-old cultural dialogue which is lodged into the very fabric of your Versace bomber jacket, or, more realistically, your cotton-blend t-shirt. You are standing on the shoulder pads of giants.